John Updike was one of my heroes, and he will be greatly missed. So it goes.

A multitude of writers discuss Updike, including Garrison Keillor, from Granta:

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, from The New York Times:

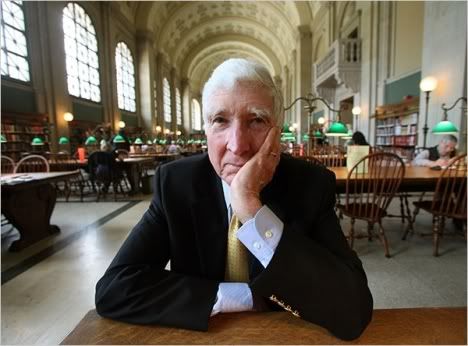

W. Earl Snyder

Requiem, by John Updike, from The New York Times:It came to me the other day:Ian McEwan, from The Guardian:

Were I to die, no one would say,

“Oh, what a shame! So young, so full

Of promise — depths unplumbable!”

Instead, a shrug and tearless eyes

Will greet my overdue demise;

The wide response will be, I know,

“I thought he died a while ago.”

For life’s a shabby subterfuge,

And death is real, and dark, and huge.

The shock of it will register

Nowhere but where it will occur.

The Updike opus is so vast, so varied and rich, that we will not have its full measure for years to come. We have lived with the expectation of his new novel or story or essay so long, all our lives, that it does not seem possible that this flow of invention should suddenly cease. We are truly bereft, that this reticent, kindly man with the ferocious work ethic and superhuman facility will write for us no more. He was intensely private, learned, generous, courtly, the kind of man who could apologise for replying to one's letter by return of post because it was the only way he could keep his desk clear.Roger Angell, from The New Yorker:

Contrary to what his work might suggest, Updike was in actual life devoted to his large family that sprawled across the generations, so why not let one of his youngest characters take the parting bow on his behalf. When Henry Bech goes up on stage in Stockholm to make his Nobel acceptance speech, he takes with him on his hip his one-year-old daughter. She wriggles impatiently through his lecture and when at last he has finished, she reaches out for the microphone "with the curly, beslobbered fingers of one hand as if to pluck the fat metallic bud". Bech feels the warmth of her skull, he inhales "her scalp's powdery scent ... Then she lifted her right hand, where all could see, and made the gentle clasping and unclasping that signifies bye-bye."

As a contributor, [John Updike] was patient with editing, and pertinaciously involved with his product: an editor’s dream. My end of the work was to point out an occasional inconsistent or extraneous sentence, or a passage that wanted something more. Almost under his breath over our phone connection, while we looked at the same lines, he would try out an alternative: “Which one sounds better, do you think?” Sighing, he would take us back over the same few words again and again, then propose or listen to a switch of some sort, and try again. All writers do this, but not many with such a lavishly extended consideration. He wanted to see each galley, each tiny change, right down to the late-closing page proofs, which he often managed to return by overnight mail an hour or so before closing, with new sentences or passages, handwritten in the margins in a soft pencil, that were fresher and more inventive and revealing than what had been there before. You watched him write.Sam Anderson, from New York Magazine:

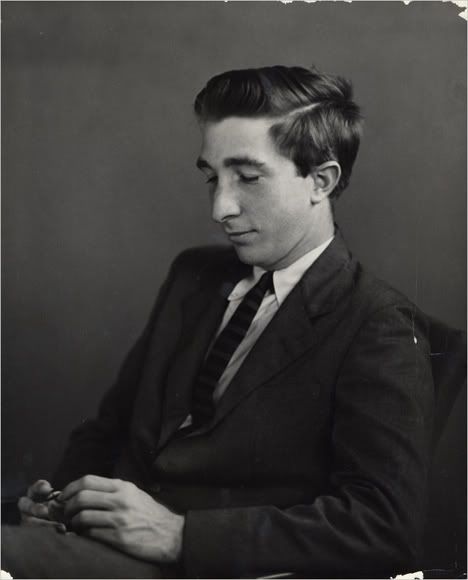

Updike’s best sentences are as funny, as stylistically bulletproof, and as present as any sentences have ever been. They’re so consistently springy and alive, in fact, that, while you’re reading them, it’s impossible to accept that he’s gone. They seem to have been written, just a few seconds ago, by the young man whose picture is on the back of the book.Adam Gopnik, from The New Yorker:

Despite the lyrical surface of his prose, Updike was a realist, as comedians must be, and never even marginally a romantic. He was genuinely unseduced by all the myths of American romanticism: gorgeous Daisys and vast sinister Western landscapes are equally absent from his books. His girls and women are real, with scratchy pubic hair, and his American landscape of car dealerships and fast-food retreats held no place for doomed, exciting, existential gunmen. He was, for all those perfect shining sentences, a realist; the sentences sing, but they don’t ennoble.Charles McGrath, from The New York Times:

What other writers, young and old, prized most about Mr. Updike was his prose — that amazing instrument, like a jeweler’s loupe; so precise, exquisitely attentive and seemingly effortless. If there were a pill you could take to write like that, who wouldn’t swallow a handful? Equally inspiring was his faith in the writing itself. He toyed once or twice with magic realism, but the experiment never really worked and he gave it up. Though he loved Jorge Luis Borges, he didn’t in his own work go in for Borgesian mirror games, and he was free from the postmodern anxiety about the fictiveness of fiction, the unreliability of language. He was an old-fashioned realist, with an unswerving belief in the power of words to faithfully record experience and to enhance it. If other writers, younger ones especially, couldn’t quite subscribe to that belief, still it was reassuring to know that there was someone who did.Sam Tanenhaus speaks with Updike [NY Times Video]

A multitude of writers discuss Updike, including Garrison Keillor, from Granta:

When I last saw him, a year ago, we were at a literary function in far uptown Manhattan, where he’d read a moving tribute to Kurt Vonnegut. He walked with my wife and I to the subway and I got to compliment him on Gertrude and Claudius, which I had just read. We rode downtown together, and a band of seminary students boarded our car and recognized him and said all the things I’d made myself not say years ago. He was very gracious with them, jokey and off-hand. He was a great man, and when he wrote me a note saying he liked a story of mine, I treasured that more than one should. He was an uncomplaining writer, a genius but also a workman, and he seemed to pick up energy in his last decade, which is encouraging to the rest of us. The Centaur is still my favourite of his books, a work of filial devotion, with the Olinger stories a close second. God bless his memory.Joseph O'Neill, from Granta:

The death of John Updike is an instant literary disaster: with immediate effect we are deprived of the three daily pages that, Sundays aside, were his to write, pages that operated as perfect verbal rovers upon even the most inhospitable critical and imaginative terrain. There will be printed posthumous delights, of course; but we can no longer find security in the knowledge that John Updike is at his desk, producing Updike.Jonathan Lethem and Joseph O'Neill discuss Updike and fatherhood [MP3]

Robert Spencer

Martin Amis, from The Guardian:He alone could hold his head up with the great Jews - Bellow, Roth, Mailer, Singer - it was entirely typical of him that, as a sideline, he became a great Jewish novelist too, in the person of Henry Bech, the hero of several of his books. That seems to me to be an essential Updike trait, never being satisfied with any limitations always demanding far more than his fair share.Gish Jen, from The New Republic:

All I can do is pay, here, my heartfelt homage to him, a great writer--protean, as many have noted, and spectacularly, tentacularly gifted--a prolific, old-fashioned man of letters, yes, but finally, I think, a writer without whom the necklace of 20th century American literature could not be judged complete. Crack chronicler of America that he was, he reminded us of the role literature has always played in our national self-fashioning even as he showed us that that role could be played aesthetically: with gorgeous writing and a cool intimacy that in his best work keeps the reader on the cusp of moral judgment.Clyde Haberman, from The New York Times:

“Once I got here,” he said of New York in the 2005 interview, “I realized that immense as the city is, your path in it tends to be very narrow. I only knew people I went to college with and other writers, and felt I wasn’t really getting a fair picture of America here. And there were too many other writers and editors and agents and people who were willing to give me ideas of what I should do with my life.”Lorrie Moore, from The New York Times:

Mr. Updike’s novels wove an explicit and teeming tapestry of male and female appetites. He noticed astutely, precisely, unnervingly. His stories, some of the best ever written by anyone, were jewels of existential comedy, domestic anguish and restraint.Richard Ford, from The New Yorker:

These, then—with my drenched, sweated-through Brooks’ suit—I was wearing as I pounded my way down Old Bond Street, headed for the Arcade and my cigar and silk finery, when whom should I suddenly look square in the eyes but John Updike—on his way God knows where, out ahead of our scheduled collegial lunch at Brown’s. And I will say that the look he gave me—because for some reason he seemed to know it was I—was a look of profoundest dismay, shifting instantly into embarrassment, and then on to sincere regret. It was a look that said, “My God, Ford, what’s happened to you? You’re soaked though, you look wild as a dingo, and you’re wearing these idiotic sunglasses. You seem like an escapee from someplace you might better have stayed. And in an hour I’m having lunch with you.”

He wrote about America with boundless curiosity and wit in prose so careful and attentive that it burnished the ordinary with a painterly gleam.Michiko Kakutani, from The New York Times:

He moved fluently from fiction to criticism, from light verse to short stories to the long-distance form of the novel: a literary decathlete in our age of electronic distraction and willful specialization, Victorian in his industriousness and almost blogger-like in his determination to turn every scrap of knowledge and experience into words.Sam Anderson, from New York Magazine:

I always go back, first, to his essays, which strike me as the purest expression of his personality: easy, sociable, curious, smart, funny, generous, and almost pathologically cheerful. He was, for my money, one of the greatest belletrists of all time — a master of the short, casual, elegant, whimsical, roving piece about absolutely anything...He could take the fruits of high culture — obscure philosophy, art history, sociological scraps — and translate it, for a wide audience, into little miracles of focused thought, all written in an elegant verbal music.T.C. Boyle, from The New Yorker:

He enchanted me. He led the way. I will miss him in the way I would miss one of the peaks outside the window here if some natural catastrophe were to take it down. There is an absence, surely, but there is the memory of what was once there—and, better yet, a full shelf of books to recollect and reread.George Saunders, from The New Yorker:

A John Updike is a once-in-a-generation phenomenon, if that generation is lucky: so comfortable in so many genres, the same lively, generous intelligence suffusing all he did. I never had the pleasure of meeting him, but, as I expect is the case with many readers, I internalized him, and am a better person for the urbane, hopeful, articulate voice he put in my head.From Ashcan Rantings:

- Updike Times Two by Charles Rhyne

- Updike: America's Man of Letters by Charles Rhyne

- Rabbit Reborn by Charles Rhyne